Jethro Tull. The name is familiar to millions of rock fans, but the music is probably not as familiar as it should be (“Aqualung” excepted). We’re talking here about a musical group that experienced massive commercial success but somehow went under the radar and did not gain membership in rock’s dubious pantheon. While the band, and particularly its cheeky flute-playing leader Ian Anderson, gained and retained a loyal following, the rest of the rock audience seems to have ended up regarding Tull with some bemusement. This is through nothing but sheer ignorance. Much like most people I talk to seem to think Rush’s Geddy Lee is frozen in time as a kimono-wearing male banshee screeching about Xanadu, when in fact for over thirty years he has been singing like a lower-toned angel and making incredibly subtle, classy music, these same people see Anderson forever as standing on one leg in spandex while tootling an overly long flute solo in a tune about a randy hobo. Such is the price of early success ― the average punter sees you as you were in your so-called “prime”, and if they don’t like that, well, you are dead as an artist to them. Needless to say, those people need to smarten up.

Jethro Tull. The name is familiar to millions of rock fans, but the music is probably not as familiar as it should be (“Aqualung” excepted). We’re talking here about a musical group that experienced massive commercial success but somehow went under the radar and did not gain membership in rock’s dubious pantheon. While the band, and particularly its cheeky flute-playing leader Ian Anderson, gained and retained a loyal following, the rest of the rock audience seems to have ended up regarding Tull with some bemusement. This is through nothing but sheer ignorance. Much like most people I talk to seem to think Rush’s Geddy Lee is frozen in time as a kimono-wearing male banshee screeching about Xanadu, when in fact for over thirty years he has been singing like a lower-toned angel and making incredibly subtle, classy music, these same people see Anderson forever as standing on one leg in spandex while tootling an overly long flute solo in a tune about a randy hobo. Such is the price of early success ― the average punter sees you as you were in your so-called “prime”, and if they don’t like that, well, you are dead as an artist to them. Needless to say, those people need to smarten up.

So what is Jethro Tull? First a jazz-rock group, then a progressive rock band, then a folk-rock band, then a hard rock band. In that last iteration I mentioned, they won the Grammy in 1988 for Best Hard Rock album and were then the subject of intense ridicule, because a rather deserving Metallica was passed over. Forgotten in all that was that Tull neither wanted nor cared about the award. I’m sure being declared a symbol of all that was wrong with the music industry did not sit well with Anderson.

Here’s the truth: in all those iterations, Ian Anderson has consistently proven himself to be one of rock’s finest tunesmiths, an astonishingly incisive lyricist and a musical explorer par excellence. Not only does he play that flute pretty good, but he plays the shit out of an acoustic guitar and has consistently surrounded himself with top musical talent to realize his visions, which, despite what you may think, are anything but airy-fairy and grandiose. Anderson’s music is earthy, gritty and smart without being overbearingly pretentious.

THE THESIS

THE THESIS

OK, that’s out of the way, for that’s just background.

As you know, “punk” was “sweeping” away the intellectual “pretensions” of all those horrible prog-rockers (detect the sarcasm, please), and while other bands were panicking and trying to write more conventional music, Anderson went in a different direction and in doing so potentially changed the face and future of English music. That others did not recognize the value of this new path is not Anderson’s fault. My argument here is that Songs from the Wood (1977), Heavy Horses (1978), and, to a slightly lesser degree, Stormwatch (1979) are trailblazing albums that not only took British folk-rock to exciting new places but offered a new hard rock vernacular to express a distinct British identity.

Bands like The Albion Band, Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span had done the initial work of taking the traditional people’s music and fusing it with the excitement provided by loud electric instruments, and often either writing new songs in the style or setting the old lyrics to their own rock-influenced music. Where Tull’s efforts differed lay in the fact that Anderson’s combo was a platinum-selling, stadium-filling prog and glam-influenced band that knew how to wield drama on a large scale (they were famous for their bizarre stage presence). They rocked hard, with almost a metallic edge at times, but also, due to the members’ impressive training and ability, could also produce pieces of intense intellectual subtlety. Anderson’s intelligence generated suites of songs that took a grounding of the traditions of British music but fused it with high-octane rock sounds to produce music that could not have come from any other place in the world.

Something to be proud of, no? You’d think so, but while the albums did well enough, a new movement of British-style hard rock was not launched, for the same reason that folk-rock and electric folk didn’t take off in the first place — the British public just had no interest in such a source of national pride, preferring instead to absorb cultural influences from America, the coolest place on Earth (apparently). Were these albums too rarified intellectually? Too subtle musically? Who knows. But the evidence of this path not taken shines from the grooves of these three albums, which I feel should be recognized for the groundbreaking work that they were. In Rob Young’s mostly excellent book Electric Eden (partially a history of the search for a British musical identity), for instance, Tull’s efforts receive one disdainful sentence. Has he not listened to these albums? Is he going with the flow of Tull-dissing that I and the band’s other admirers find so distasteful?

In any case, I’m setting the record straight here. If you like folk music, folk-rock, progressive rock, or just happen to love intelligent rock music, you should check out these albums.

THE ALBUMS

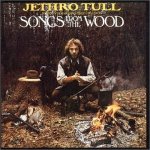

Songs from the Wood

Songs from the Wood

Coming off a dry spell with the not-so-good (and horribly titled) album Too Old To Rock ‘n’ Roll: Too Young To Die!, it looked like Tull might be a spent force. Instead, Anderson changed direction. He’d been involved with folk-rock before, executive producing Steeleye Span’s Now We Are Six, and had evidently developed a taste for the stuff. The band he’d assembled by this time was perfectly skilled for the job, including two keyboard players, stalwart John Evan as well as David (now Dee) Palmer, a classically trained musician who could play any old archaic form. Powerhouse drummer Barriemore Barlow, mega-axeman Martin Barre and bassist John Glascock (ex of flamenco-rock band Carmen) fleshed out the lineup. Barre in particular really stepped up to the plate on these albums, seamlessly integrating the rhythms and melodies of British music with his usual bluesy licks, just like he invented all this stuff.

The album starts with a bold statement of intent, the title track, in which Anderson regales us with a selection of traditional English country imagery, set to an a cappella tune and rich harmonies, followed by complex, playful rhythms, layered keyboards and Barre’s tasteful guitar flourishes, before setting off into a dramatic middle section then resolving back to the original tune. As a manifesto, it’s perfect.

“Jack in the Green” is a fun acoustic ode to some sort of sprite — again Anderson is borrowing from folklore but twisting it to his own devices.

“Hunting Girl” takes the subject of many’s the traditional ballad, sex between social classes, but turns it on its head — in this case the rich lady is the aggressor (as in the well-known “Matty Groves”) and deepens the story, detailing the poor peasant’s fright and puzzlement at being used in such a way by the lady of the manor. So it’s a sort of social commentary. And it’s fused with some super hard-rock riffing to boot. Really ripping stuff.

“Velvet Green” is a lusty ode to love in the outdoors that goes through an astonishing set of permutations, starting off with a Baroque-influenced piece (no doubt Palmer’s influence at work) before morphing into a moody, strummed middle section that approaches acid-folk at times. “The Whistler” is a dramatic, flowing song in which Anderson has invented a mythical persona for himself in the title. Alternately earthy and rocking, it kind of summarizes the album.

The long “Pibroch (Cap in Hand)” begins with a veritable heavy metal suite of Barre’s guitars layered over each other playing a Scottish-style melody, then changes to another moody ballad, this time a rumination on rural adultery, featuring another Baroque-style midsection.

“Fire at Midnight” ushers out the album with a cozy setting of a rural idyll, sitting by a fire with the city far away and all cares put to rest.

This album is a wonderfully cohesive piece of work that sets an impressive mood — the feel is ancient, even though the sounds are loud and proud. What a manifesto for the traditions of British music!

Heavy Horses

Heavy Horses

The follow-up album deepens Anderson’s dedication to pursuing this path, if anything. Curiously, he has changed his vocal style for this record, mostly abandoning the rich smoothness of his usual style for a lusty, gutteral sound, as though he’s personifying the earthy working classes. The production is cleaner, too, and rougher, more down to earth.

“And the Mouse Police Never Sleeps” tells an Animal Farm-ish tale of oppression through the eyes of small woodland mammals! It doesn’t sound like it should work, but it does.

“Acres Wild” continues some of the themes from the first album, an exhortation to make love on the hills, but this time the music sounds sloppier and rootsier, presaging the Celtic rock made by younger bands in the eighties that found a good deal of success. Except this tune has a string section too! “No Lullaby” is a bit incongruous, a lengthy power-prog piece with high-octane riffing and violent imagery. It’s fun, though, and does contain the greatest, longest drum fill I’ve ever heard (at 0:45 for you drum-heads).

“Moths” is about just that. Moths. “Journeyman” has a Victorian feel, a sepia-toned story of a lonely fellow travelling by stinky British rail. “Rover” matches “The Whistler”, a hit-single quality slice of ultra melody and broken-chord acoustics, an ultra-catchy electric guitar motif and lyrics that are an ode to wanderlust, which I assume we all feel at times. I sure do. A wonderful song.

“One Brown Mouse” is about just that. A mouse. Based on the poetry of Burns, of course. Good fun.

These tunes are all good, but let’s get to the monolith that is the title track of Heavy Horses, a nine-minute lament for the disappearance of the shire horse. But it’s not just that; it’s about the death of the old world, sort of a Lark Rise to Candleford in a song, and the challenges of living a modern technological life, no longer connected to the soil as our ancestors were. I find this incredibly prescient and relevant, considering how computerized and artificial 21st century life is. Anderson is using the horses as a symbol for a lost, slower, more peaceful way of rural life. The lyrics are pure poetry during the piano-driven intro ballad, and in the rollicking middle section you really can feel those heavy horses running free, waiting for “the day when the oil barons have all dripped dry, and the nights all seem to draw colder” and we will once again call on their “strength” and “gentle power”. Can a song about horsies make Make Your Own Taste emotional? Yes, it can!

This album (and that piece particularly) is one of the supreme achievements in British music.

Stormwatch

Stormwatch

The tires started to come off, unfortunately, by this time. The tragic early death of John Glascock no doubt cast a pall, but also, Anderson appeared to fall victim a bit to that streamlining that other progressive bands were doing, trying to come up with snappier, shinier tunes, which he would pursue further on A and also, more successfully, on Broadsword and the Beast. A number of the songs on this album are not particularly successful, often due to an attempt at topicality that made them sound dated almost out of the gate, as on the opener, “North Sea Oil”. Others, such as “Something’s On the Move” and “Old Ghosts”, just aren’t up to his quality standards.

Still, there are a number of gems on this album that make it good enough that you shouldn’t give it it a pass. “Dark Ages” is a prog monolith of nine minutes that is topical in a good way, presenting a nightmare apocalyptic scenario that is perfect for Anderson’s wry, cynical worldview (as presented so famously on Thick as a Brick). It’s also musically inventive and allows Barre to really shine in a weird but tuneful solo.

“Orion” is an edgy but sentimental prog-folk ballad that sounds tailor-made for the eighties. “Dun Ringill” is one of Anderson’s most spectral acoustic songs, misty and moody. “Flying Dutchman” is a sweeping, melodic seafaring tale with a Celtic bent and some dramatic piano playing. And the instrumental “Elegy”, a classical-style piece, sounds like (though I don’t know it is a fact) it could be a fond send-off for the departed Glascock.

CONCLUSION

Well, I’ve spent all these words and taxed my little brain to try to express to you what a great achievement this little body of work is. These three albums are criminally underappreciated both by progressive rock fans and folk-rock fans, probably because they don’t fall enough into either camp to be comfortable. But if you are adventurous, you will try ’em out and you will like ’em.

Agreed, “Heavy Horses” is poetry worthy of Hardy; I’ve never looked at a draft horse the same since. I don’t know Stormwatch as well as the other two albums – I’ll have to check it out.

LikeLike

They are all great albums, but my personal favourite is Songs from the Wood. I think Pibroch is criminally underrated. Barre has always delivered at least one monster piece of guitar spanking on each album (listen to the axe-work on Steel Monkey). Barlow was one of the best drummers in rock music (the drums on No Lullaby being one of my favourites). Glascock’s bass playing seemed to improve with each release. The twin keyboard salvo provided by Evan and Palmer added a lot of weight and substance to the songs, and Anderson’s writing never really disappoints (I still enjoy listening to the more concise songs presented on A). A fine trilogy.

LikeLike

Great remarks- I also like the A album.

LikeLike

I think ‘A’ is also underrated. Jobson made some great contributions to the album, and the other musicians on the album were no slouched either.

LikeLike