Popular music history is scattered with the ruins of careers that never quite took off, mouldering old LP sleeves found in attics, albums recorded by people who no doubt thought that garnering a record contract would lead to fame and glory, or at least some royalties and a performing career. Most of those people were wrong. However, the appetite of collectors for collecting all the detritus of recorded music history then sifting through it for gems has unearthed some great music put on vinyl in the 1960s and ’70s.

Popular music history is scattered with the ruins of careers that never quite took off, mouldering old LP sleeves found in attics, albums recorded by people who no doubt thought that garnering a record contract would lead to fame and glory, or at least some royalties and a performing career. Most of those people were wrong. However, the appetite of collectors for collecting all the detritus of recorded music history then sifting through it for gems has unearthed some great music put on vinyl in the 1960s and ’70s.

One artist who started in obscurity and ended up an icon, decades after his death in 1974 at age twenty-six, is Nick Drake, who definitely went from 1973’s zero to 2000’s hero in quite astonishing fashion. In Drake’s case, it likely never would have happened without the advocacy of his old record label man from the seventies, Joe Boyd, who kept Drake’s LPs in print for all those years. That, in fact, is how I became a fan around 1990, the time when I was collecting all things folk-rock on Boyd’s Hannibal Records. During Drake’s own lifetime, his records did not sell well at all. It’s a testament to Boyd’s generosity (and that of Chris Blackwell of Island) that he even managed to get three of them out. As a teen, along with Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny’s trademark melancholy and John Martyn’s unguarded soulfulness, Drake’s music became the soundtrack to my isolation and a great source of solace.

All the hype and legend aside, it’s the otherworldliness of Drake’s elfin music that is so appealing — while Fairport Convention and their ilk unearthed two hundred-year-old traditional songs, Drake’s lyrics, intoned in his soft voice, conjure up visions of a magical, misty walled garden that the ills of industrialization have never touched — a fairyland as in the fiction of William Morris or Lord Dunsany. Where the modern world enters his music, it’s always as a looming, almost evil presence threatening to destroy a bucolic idyll.

A decade after my discovery of Drake’s music, I was watching TV and a car commercial came on. My jaw almost fell off my face when I recognized the title track of Drake’s last album, Pink Moon, a record usually referenced as the cry of a soul in serious trauma. Selling cars? I was disgusted and horrified at this cheapening of a great legacy. However, the commercial somehow sparked a massive upswell of interest from indie hipsters in the enigmatic Drake’s work. And of course, the fact that Drake was both long-dead and had been enigmatic while alive no doubt contributed greatly to that. I remember a Drake song being featured in the movie The Royal Tenenbaums, a painfully, knowingly pretentious movie and the only one I ever walked out of. But the fact that hip dudes were now choosing Nick’s songs for their oh-so-cool movie soundtracks was quite telling.

I’ve never been one to crow when the world picks up on some musical passion of mine, well after I did. In fact, I was one of those people who became annoyed when the world at large invaded my own little galaxy of obscure musicians who spoke to only a chosen few. That might have made me the most annoying kind of hipster of all.

Be that as it may, Nick Drake is now massively popular and influential, forty years after his sad demise. And I’m no longer a sad, depressed teen looking for music that reflects his own lonely mindset. After taking a bit of a break from Drake’s music, I have undertaken some almost-fortieth anniversary listens to his stuff with a more dispassionate ear.

If we’re being honest, as I said, part of the appeal of Drake lies in the enigma. I read Patrick Humphries’ biography of the man, and it struck me that I have never read a biography that contained less hard information about its subject. It’s like no one actually knew this kid, so a lot of the narrative is sheer conjecture. He was painfully shy, he was quiet, he could be fun though, he might have been gay, no he was straight, but no one really knew — no one knew what was going on in Drake’s mind, or if they do, they’re not saying. We don’t even know if he really killed himself — his family says not.

Silent Nick Drake is the ultimate mystery of a person, so we have to scour his albums for clues. There’s no doubt of one thing: he was supremely talented, with incredibly poetic lyrical and melodic gifts, an ethereal voice and a mind-blowingly complex acoustic guitar style involving his own tunings.

However, I’m going to hang myself out to dry here and suggest that none of his albums are perfect, and that Drake’s best work was never recorded. Mind you, had he lived and gotten his act together, he might today be putting out horribly cheesy albums of standards that make Rod Stewart’s recent efforts sound good. You never know, and that’s what’s appealing about the “dead rock star” (or unheralded genius): He is forever frozen in time, an unanswered question and a finite body of work for us to comb over, eternally youthful as well, which is doubly appealing. We are, after all, turned off by age and decay, being a poor, sentient species in terror of our own demise.

Again, Nick Drake is the ultimate such example of transcendent youth — tragic, unknowable, unsuccessful but gifted, the butterfly captured in crystal of the utopian sixties idyll, and he’ll be that way forever. This explains why he seems to stand much taller than the other myriad “obscure” singer-songwriters. Why is there no massive cult of Bridget St. John? Or Bill Fay (who does have a small one)? Or Keith Christmas? Or even Sandy Denny, as popular as she remains? The answer in the latter case may be that Denny was too knowable; she played and sang on at least a dozen albums, lived and boozed large, and her end, though tragic, was totally accidental.

Nick Drake is the ultimate in detached cool — wonder what he’d think about that?

Let’s look at his three LPs (The Time of No Reply LP compiled from demos after his death is nice, but not representative, as are other archival releases).

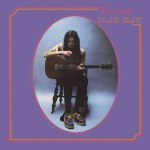

Though the first, this is probably the finest of Drake’s albums. It fits perfectly in some ways with the zeitgeist of 1969, a delicate compendium of pastoral yearning — the rich green on the cover says it all. I’m sure Drake had a say in the production of his albums, but in my opinion the elaborate arrangements might not have been what he would have chosen himself, given the choice. Too often they overwhelm the delicacy of his songs, though not so much on this album. Harry Robinson’s Debussy-esque wash of strings on the transcendent “River Man” combines with the romance of the lyrics and the stately rhythm of Drake’s guitar to result in the finest production of Drake’s career. Robert Kirby’s arrangements of “Fruit Tree” and “Way to Blue” are more baroque, but still fitting in their archaism. The lyrics of the former remain chillingly prescient, a rumination on the fickleness of fame and how it comes for many too late — as it would for Drake himself. Other arrangements are not quite as successful, such as the lounge jazziness of “Saturday Sun” and the overly busy congas on “Cello Song” (these are still pretty dang good recordings). To me, Drake would have been served by arrangements that at all times would capture the ethereal nature of his songs and voice. If he were recording years later, hell, I might have draped it all in synth pads and mellotron samples (guilty!). Imperfections aside, the consistently high quality of the songwriting and the more fitting production make this Drake’s finest LP.

Most consider this Drake’s finest album, but I disagree. The most commercial of them, yes, and still a wonderful album, but not even close to the first. The reason is that efforts were made to jazz Drake up sort of like a spacy Van Morrison, and while he may have loved jazz and blues, I’m sorry, Nick was no jazzier than I am, and I’m as unfunky as it gets. With that whispery voice, yearning songs and inimitable guitar style, he succeeds on songs like “Northern Sky” and “Fly“, the former being one of the most beautiful “love” songs ever written, surprising coming from a man who was apparently a sexual enigma and was never known to have a relationship in his lifetime. Perhaps that’s what created the aura of idealized love represented in the song. Those two aforementioned songs are also arranged very well, quite tastefully, with John Cale providing the instrumental atmosphere. “At the Chime of a City Clock” is the only example where Drake’s songs and jazziness work well together, with lazy sax, elegiac strings and a subtle beat creating a backdrop to Drake’s paranoid urban vision — slow burn jazz. “Poor Boy” sounds terribly forced, from the gospel-style backing vocals to Drake’s lame attempt to sound more cheerful. Similarly, the upbeat-sounding “Hazey Jane II” and “One of These Things First” are to me mostly throwaway — they just don’t ring true. Still, because of the really great stuff Bryter Layter is still a classic. Maybe if they wanted it to sell, a more inspiring image than that of Drake, looking miserable and shadowy while contemplating a pair of shoes, would have been a good idea.

Strangely, this is the album that the Nick Drake legend is founded on. Suffering in the lowest pits of what was likely chronic depression, Drake turned up one day at the record company with the masters of this short LP, dropped them off, and that was it — love this or leave it. This is unadorned Drake, but not in the way you’d ideally want — from a less tragic guy (we don’t wish misfortune on others now, do we?). But yes, the legend of this album is well-founded, for in these grooves you can hear a man making himself do this, gritting his teeth and pouring the darkest visions from his tortured soul. This is not a confessional, however, a set of complaints or whining. Drake was too private for that, still using symbolic language to convey his desperation. And the stripped-back nature of it all, just voice and guitar up front, really lays things bare. It’s astonishing to listen to, and there’s not much else like it out there. It’s at its best when most coherent, as on the tense “Parasite” the heartwrenching “Place to Be“, and the slightly more upbeat “From the Morning“, but really the album is an entire listening experience, best not sampled, more of a hazy limbo you visit for half an hour then resurface to find yourself changed. Is the massive public interest in this revelation of despair a bit ghoulish? Probably, but such is the nature of popular culture. I’m sure for every person who’s picked up Pink Moon because of “dead legend” hype, there are several others who were attracted to it because they are searching for true honesty in music, which is hard to find. You’ll never find a more honest album than this, the last cry from a soul who wanted to be understood and wanted to alter people’s mindset through his music.

Ironically, forty years later and through the selling of luxury automobiles, he has done — and has influenced far more people than he ever could have imagined. So, put aside all the hyperbole, the legend, and the conjecture and just give these LPs a listen. They are glimmering jewels from the most creative era of popular music.

A lovely review of Drake’s legacy. I discovered Drake from “Bumpers” in 1970 as a 14 year old and “Hazey Jane” with its Richard Thompson guitar work still sends an adrenaline rush through these ancient bones. Lovely stuff.

Linda Thompson (nee Peters) had a fling with Drake as well as his erstwhile boss, Mr Boyd. Of course, she ended up with RT. Not sure how much of a relationship it was though.

Thanks for the piece – Nick Drake still comes up regularly on my iPod, I’m so glad Chris Blackwell made sure that it was always available. I still have my original vinyl albums. Trevor Dann’s book is also worthwhile reading along with the one by Patrick Humphries.

LikeLike

Thanks! Yeah, I remember now from the book that she says she dated him – but it didn’t go very far!

LikeLike

I remain convinced that his thumb was the crux of his fingerpicking genius. I think it was Joe Boyd’s book that described one of Drake’s few live appearances as a man with one guitar and a different tuning for each song he played. Which no doubt endeared him to the pub crowd.

From the Morning is the song that has been most important to me since my mother passed away last year. I’m not sure why, but thanks to Nick and you as well for the wonderful site. Thanks for the Spherelus and Kumea Sound recommendations in particular. LLOH (long live Ollie Halsall).

LikeLike

Thanks for the wonderful comment. Yeah, he was thumb-heavy indeed.

Love Halsall’s work with Ayers.

LikeLike

I only discovered Nick Drake 18 months ago via a cover version of River Man on a website. Last month I found these albums in HMV all for £2.99, so I snapped ’em up. Some of his songs remind me of early John Martyn. Mr Drake was a real talent.

LikeLike

Yep, he was. A gentler version of Martyn’s jazziness. Apparently they were friends.

LikeLike

What a fab summary. I couldn’t agree more about the Bryter Later cover-what were they thinking? Especially given their efforts to make it a cheerier album. Beggars belief! They also completely messed up the track listings and published unused verses on the Five Leaves Left cover. However, John Boyd was fantastically supportive and Nick had so many amazing opportunities, it’s so sad that things went so wrong for him internally, and such an enigma. Thank you for this!

LikeLike

Thank you! Glad someone found this article. Wasn’t one of the better-read ones, surprisingly.

LikeLike